Top spots to see some of London’s best brutalist architecture.

There’s no doubt about it, brutalism is the architectural equivalent of Marmite.

Despite softening attitudes to the post-war architectural style, the sight of London’s brutalist buildings elicits ecstatic raptures from some, but a near visceral hatred from others.

For the avoidance of doubt: we’re very firmly on the ecstatic rapture side of the argument.

The clean lines and severe structures of the brutalist style helped to shape the London of the post-war period in a way that felt new and modern.

Today, those buildings are still some of the city’s most interesting to observe – The National Theatre, The Barbican, The South Bank Centre – they’re uncompromisingly different, unafraid to break with the ornate, decorative traditions that came before them.

Luckily for all of us, there’s no shortage of Brutalist architecture in London. Photographing this piece reminded me that sure, London’s known for its history and culture – but when it comes to Brutalist architecture, well, it isn’t afraid to strut its stuff.

From well-known buildings such as Trellick Tower to less-discussed gems like The NLA Tower, it’s time to discover beautiful Brutalist London.

What is Brutalism?

Brutalism is a post-war architectural style that emerged in the 1950s and thrived until the 1970s. It’s defined by its use of poured concrete or brick to create monolithic, blocky and severe styles and geometric structures.

Brutalist architecture sought to showcase the materials buildings were constructed of, as well as the functional components of its structures.

As such, things like lift shafts, ventilation ducts, staircases – even boiler rooms, were integrated into the fabric of the building in ways that celebrated them as distinct features rather than hidden away.

In London, it was used heavily in reconstructing the city in the aftermath of World War II – particularly for social housing and government buildings – though as it grew in popularity its uses extended beyond these spheres.

Best Brutalist Architecture in London

The Barbican

Chances are that if you think of Brutalist buildings in London, you will think of the Barbican Centre. This Grade II listed building is Europe’s largest multi-arts and conference venues and one of the city’s most ambitious post-war architectural projects.

It was developed from designs by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon. Intended to help boost the number of people able to actually live within the City of London and regenerate Cripplegate – an area devastated in World War II, it opened to significant acclaim in 1982.

Venture into the complex and you’ll find a labyrinth of pedestrian walkways, residential buildings in addition to the two main buildings of the Barbican Centre itself. There’s even a gorgeous conservatory in there, if you know where to look.

Trellick Tower

Ernӧ Goldfinger’s uncompromising high rise, Trellick Tower looms over Ladbroke Grove. Completed in 1972, the 31-storey tower is one of London’s best-known (and by some, most reviled) Brutalist buildings.

The unique design combines a main block of social housing with a service tower, connected via covered walkways every three floors. The only curvature is found in the cantilevered boiler house atop the service tower.

Royal Festival Hall

The Royal Festival Hall is the largest venue in the Southbank Centre. Designed by Robert Matthew with Leslie Martin and Peter Munro, it was designed to represent the optimism and forward-thinking attitude of postwar Britain.

In fact, the avant-garde structure of the building was also meant to reflect the programme of events happening inside – creating a synergy between form and function that is reflected elsewhere in the building. For example, in the interior’s “classless-designed” bars and restaurants and the open foyer policy that allowed public access during opening hours.

National Theatre

Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre is a splitter. In 2001 it managed to earn places in a Radio Times poll of both the most hated and most loved buildings in Britain.

Another prime example of the grand public sector architecture that dominates London’s Brutalist scene, the structure is built around the concept of making theatre accessible to the masses. As such the large Olivier Theatre seats 1,160 people, alongside two smaller theatres that also seat significant numbers.

It’s no surprise that the building itself is unashamedly grand, ornamented with a complex layering of concrete that reveals itself in stages.

Alexandra Road Estate

The Alexandra Road Estate winds alongside Camden’s railway line, a swooping swish of striking architecture and intricate design that reflects Brutalism’s utopian vision.

It was designed by Neave Brown, an American architect who was then working in Camden Council’s architecture department. Brown also designed the Dunboyne Road Estate and Winscome Street Row Houses in Camden – which are all listed.

Brunswick Centre

Standing in stark contrast to the proliferation of Georgian houses that surround it, The Brunswick Centre is a multi-purpose residential building and shopping centre in Bloomsbury.

The cream and sky blue colour scheme of Patrick Hodgkinson’s design provides a different take on Brutalism. There are the same sharp lines and geometric shapes, but they’re tempered by the aesthetically pleasing palate rather than the dark grey more commonly associated with the form.

The centre was supposed to be part of a larger development razing its way through Bloomsbury, but in the end, only The Brunswick section was built. I’m grateful it was though – the light-filled walkways and symmetrical designs are some of London’s best.

Read The Full Guide: The Brunswick – Brutalism in the Heart of Bloomsbury

Royal College of Physicians

Though it might not be as well-known as Lasdun’s Brutalist masterpiece, The National Theatre, his design for the Royal College of Physicians is one you should see nonetheless.

The Grade I listed building overlooks leafy Regent’s Park and sits amidst the area’s palatial Regency architecture, somehow managing to be sympathetic to both whilst also standing out as a modernist masterpiece in its own right.

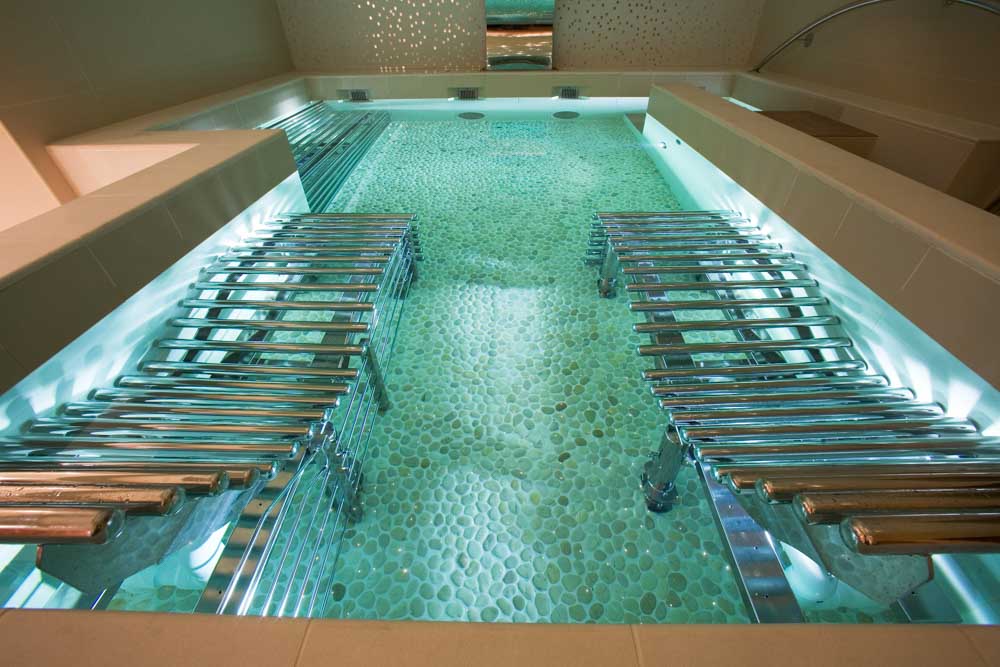

The Standard

Softer and curvier than the other buildings in this guide, The Standard is Brutalist London done differently.

It was the former Camden Town Hall Annexe (and the home of the architecture department behind developments like the Alexandra Road Estate), now it’s a swish hotel.

There’s no mistaking the building’s pale Brutalist concrete frame, it’s ambitious design thrown into relief by the Gothic buildings of St Pancras looming in the background.

Centre Point

Richard Seifart wielded unmatched influence over the London skyline – but not everyone loves the results. Take Centre Point as an example – unveiled in 1966, it was one of the tallest buildings in London… and one of its most hated.

Famously underutilised, it’s recently been transformed into a block of luxury apartments.

Brixton Recreation Centre

So many times was Brixton Recreation Centre nearly a failed project, it’s sort of a miracle that the building even exists today.

Work on the recreation centre began in 1971 and dragged right on through to 1985. During that time the project was stalled by labour disputes and political struggles in Lambeth council during the late 70s and early 80s. The project was nearly abandoned several times.

By the time the recreation centre was completed the cost of the project had spiralled out of all control, ballooning to a massive 12 times more than was initially planned. In spite of all that Brixton got a rec centre and we got another slice of brutalist architecture – one that is today, Grade II listed.

78 South Hill Park

Hampstead isn’t all rolling heaths and quaint, cottage feels. It’s also home to a brutalist building with quite an origin story…

As it goes, the architect behind the project, Brian Housden had gone to visit influential Dutch designer Gerrit Rietveld. It seems Housden was somewhat in awe of the Dutch master as when Rietveld asked him to see designs for his Hampstead house, Housden became shy and ashamed of his work.

When he got back to London Housden redrew his plans to be more avant garde and came up with the building that you can see today at 78 South Park Hill.

One Kemble Street

By doing away with, to some extent, the Brutalist’s straight edges and hard lines, One Kemble Street makes itself into a fine example of the brash, brutalist architecture of the 60s – one that shows little care for the buildings around it but stakes a big claim to its landscape.

The cylindrical structure was once home to the CAA or Civil Aviation Authority and became Grade II listed in 2015.

It’s been allowed to decay a little over the years but one pro of building with concrete is that it’s not decayed much. In 2022 Seaforth Land was contracted to repair and refurbish the structure which is expected to be made into fancy offices, and possibly a retail centre.

Brutalist London Practical Tips and Map

- Here are a couple of walking tours that will take you around some of London’s top brutalist spots. In no particular order:

- Most of London’s brutalist buildings are open to the public. Be sure to check out what’s going on inside, it’s just as important as the exterior.

- In some cases, like the Royal Festival Hall and the National Theatre you can even enjoy performances, go for dinner, or enjoy a cocktail or two in the buildings.

- If you’re walking from place to place, take good shoes. The distances will add up

Loved this post! My uni was a concrete brutalist hulk not unlike the Barbican, so I have a soft spot for the style 🙂 I adore the Barbican and did not know The Standard building – thanks for N excellent list!

Thanks Jeanne, I never understand how people can hate it – it’s so in your face yet beautiful at the same time. Glad you found a new spot to check out too, it’s a looker!