It’s time to discover (what’s left of) Samuel Pepys’ London. The history of London’s most catastrophic event, the man who recorded it and where you can pick up his trail.

Few people have passed down such a complete picture of their time as Samuel Pepys. And few people have done so at such an interesting juncture in history.

Pepys’ London was one of filth and disease that we imagine when we think back to life in the 1600s. A London of Tudor structures stacked lop-sidedly together where animal fights were popular entertainment and you’d be lucky to make it to adulthood.

It was also a London of great upheaval. Being born in 1633, Pepys was an adult through the later parts of the Civil War – even attending Charles I’s execution – Cromwell’s republic and its collapse.

Pepys’ London, it turns out, was also especially flammable. The Great Fire of London gets great treatment in his diaries and his work is one of the best sources on the subject.

The man has made a massive impact on the way we understand the event. If you’re here, there’s a high chance you’re a London history lover.

Strap in to find out what Pepys had to say, and where you can follow his trail in London today.

Who was Samuel Pepys?

Samuel Pepys (pronounced: Peeps) was a lot of things. He was an Administrator of the Navy and an MP, a womaniser, dilettante, and sufferer of painful bladder stones.

That’s not all: He was President of the Royal Society, great friends of Sir Isaac Newton and Sir Christopher Wren, a lover of wine and, of course, a Londoner.

In spite of his illustrious accolades, it’s his diaries he’s best known for, leading Pepys to go down in history as one of the greatest diarists of all time and a primary source on Reformation-era London.

Pepys’ Diaries

Pepys’ began his diaries on the first day of the year 1660 and kept the habit up for a decade, in the process chalking up around 1,250,000 words and six volumes.

Pepys was an extremely talented chronicler of his times. His eye for details always seems to land on the illuminating, and describes fantastically a sense of life in the times of Charles II’s London.

He wrote the diaries in shorthand and spared no detail about his personal life, which includes many sordid meetings with actresses and ladies of high society. It’s partly because of Pepy’s candour about his exploits that he’s considered such a rock-solid, reliable source – he’s honest to a fault.

It’s not all slap and tickle with the Dutchess, though. Pepy’s lived through many of the major events of his time. England’s last plague. The restoration of the Monarchy. The Great Fire of London – and he wrote about them in detail in his diaries.

It’s the latter that interests us today.

The Great Fire of London

Samuel Pepys first hears of the Great Fire on the 2nd of September 1666 when he’s woken by his maid at 3am to news of “great fire they saw in the City”.

Slipping on his “nightgowne,” he goes to the window and assesses that the fire is somewhere around “Marke Lane” (now just Mark Lane – speakers of ye olde English had a knack for sticking an E on the end of words).

Not seeming too worried about the blaze, Pepys goes back to bed and sleeps until the reasonable hour of seven o’clock when he gets up, dressed and goes down to Tower to get a closer look.

Pepys’ Writings

It’s at this time we get the first instances of Pepy’s humanistic eye and penchant for detail that brings the scene to life.

“Everybody endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging into the river or bringing them into lighters that layoff; poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the water-side to another.”

He even spends time dwelling on the fate of London’s (still) ubiquitous bird.

“And among other things, the poor pigeons, I perceive, were loth to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconys till they were, some of them burned, their wings, and fell down.”

His writings continue like this for several days, chronically the panic and confusion as the fire burns “with infinite fury”. Pepys, though, was sprung into action – one thing that defines the life of the man is his devotion to office.

He rushes over to Whitehall to consult with the king, explaining the severity of the situation – much to the surprise of Charles II and his consorts, and entreats the king to pull down houses around the fire to stop it spreading further – advice the Charles takes.

In spite of his efforts the fire continues to spread and Pepys’ concerns turn to his own home and family that are now at risk of being consumed in the fire and orders his belongings to be packed, taking in a now-homeless friend on the way.

Pepys sends his valuables and, most importantly for us, his diaries to Bethnal Green and escorts his wife to Woolwich with the rest of the family’s salvageables. A man ever to have his priorities right, one of the items he chose to save was a wheel of parmesan cheese that he buried in the garden to keep safe.

The Aftermath

The accounts woven between his narrative of escape paint further horrifying scenes and illustrates how utterly the fire would have wrecked the functioning of normal society. At one point Pepys writes a letter to his father, we assume to let him know the family is OK, but finds that the post office has been burnt down when he tries to send the letter.

The thing that really hits home about passages like that is the fact that Pepys was a Londoner. He was born and grew up in the city and, apart from a few education hiatuses, spent his whole life there. This is the account of a man watching his home burn.

By Friday the 7th, the fire had been put out and most of London wrecked. Pepys talks of the “miserable sight of Paul’s church; with all the roofs fallen, and the body of the quire fallen into St. Fayth’s” and “Fleet-street, my father’s house, and the church, and a good part of the Temple the like.”

The destruction was total and he says in one early passage, “it made him weep to see it.”

What Remains of Pepys’ London

As you can imagine, most of Pepys’ London is long gone. But there are still some sites to see if you know where to look…

All Hallows By The Tower

A church has stood on the site of All Hallows since the 7th century and has obviously changed skins a few times since then. It holds significance to Samuel Pepys for two reasons, the first being that he lived around the corner on Seething Lane.

Given the importance your local church played in the community in those days, we can be fairly confident Pepys would have known the place.

He certainly went there, recording in his diaries the view from the steeple as London burnt.

“I up to the top of Barking steeple, and there saw the saddest sight of desolation that I ever saw; every where great fires, oyle-cellars, and brimstone, and other things burning… … as far as I could see it”

Seething Lane

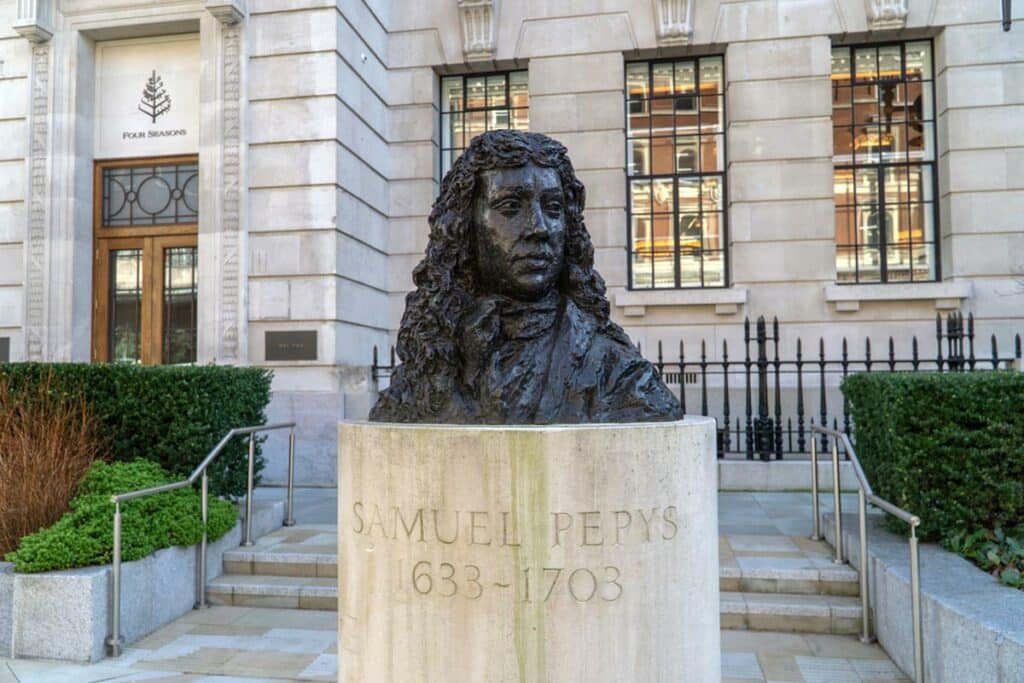

As we’ve mentioned, Pepys lived on Seething Lane. His house is long gone, but he is commemorated with a bust in the gardens along the road.

Pepys Lived on Seething Lane from 1660-1674, meaning that many of his diaries would have been written on this site.

St Olave’s Church

St Olave’s, another church just around the corner, plays an even more important role in Pepys’ life. It’s the place he was buried.

Pepys worshipped at the church with his family and even funded the building of an extra gallery. He also knocked through a special doorway to the building next door – his offices – so that he could come and go with ease.

A bust of Pepys’ wife, who died before her husband, can still be seen in a top corner of the church, looking down at the pews where her husband liked to sit.

Tidbit: Dickens also knew the church, though for different reasons. The graveyard’s gate was, and still is, decorated with a macabre trio of skulls that put the shakes in the author. He would frequently refer to the place as the church of St. Ghastly Grim.

St. Brides Church

A place of life and death, Samuel Pepys was baptised at St. Brides on the 3rd of March 1633. He was one of eleven siblings, several of whom didn’t make it to adulthood. One of his brothers is buried here.

Round the back of the church in Salisbury Court you can find a plaque that denotes the house where the man was born, now long gone.

The plaque states the date of his birth as 1632 when in fact it was 1633. This is because of changes in the calendar much later on that shifted the start of the year back from March to January.

12 Buckingham Street

This address in Covent Garden is the only surviving house that Samuel Pepys lived in and is commemorated with a bronze – yes, bronze – plaque between two first-floor windows.

Pepys lived here from 1679 after a spell imprisoned in the Tower of London on charges of selling naval secrets to the French. The charges were dropped and he was released.

It was here that Pepys would be at the height of success in his career and build his famous 3000-strong library, now housed in Magdalene College, Cambridge. He would end up moving a few doors down to number 14 after a fire scare.

Pepys’ House

Though Pepys never lived at this house on the Southbank, he did write about the bear-baiting pit that it was built over. Bear baiting was a popular sport at the time and his diary’s accounts are nothing short of grisly.

The house is now totally tarted up and was on the market for £3.5 million back in 2018.

Monument to the Great Fire of London

While you’re on a Samuel Pepys tour, make sure to check out the Monument to the Great Fire of London – built by London’s finest, Sir Christopher Wren. Take a tube to Monument Station and you’ll find it by one of the exits.

The monument was built in 1677 to commemorate the blaze, on the site of the first church to be burnt down by the fire. Standing at 62 metres high, it sits 202 metres west of where the fire started on Pudding Lane.

Exploring Pepys’ London: Practical Tips

- Pepys’ London was a much smaller place than the city we know today and so many of the places mentioned above are within a short walk of each other. Check them on the map below and you’ll see a straightforward route to tour them all.

- Pepys’ diaries are published under the title The Diaries of Samuel Pepys – A Selection by Penguin – though there are many other variations thereof – and are essential reading for anyone interested in London history. We couldn’t recommend them enough.